By Jared Harding Wilson

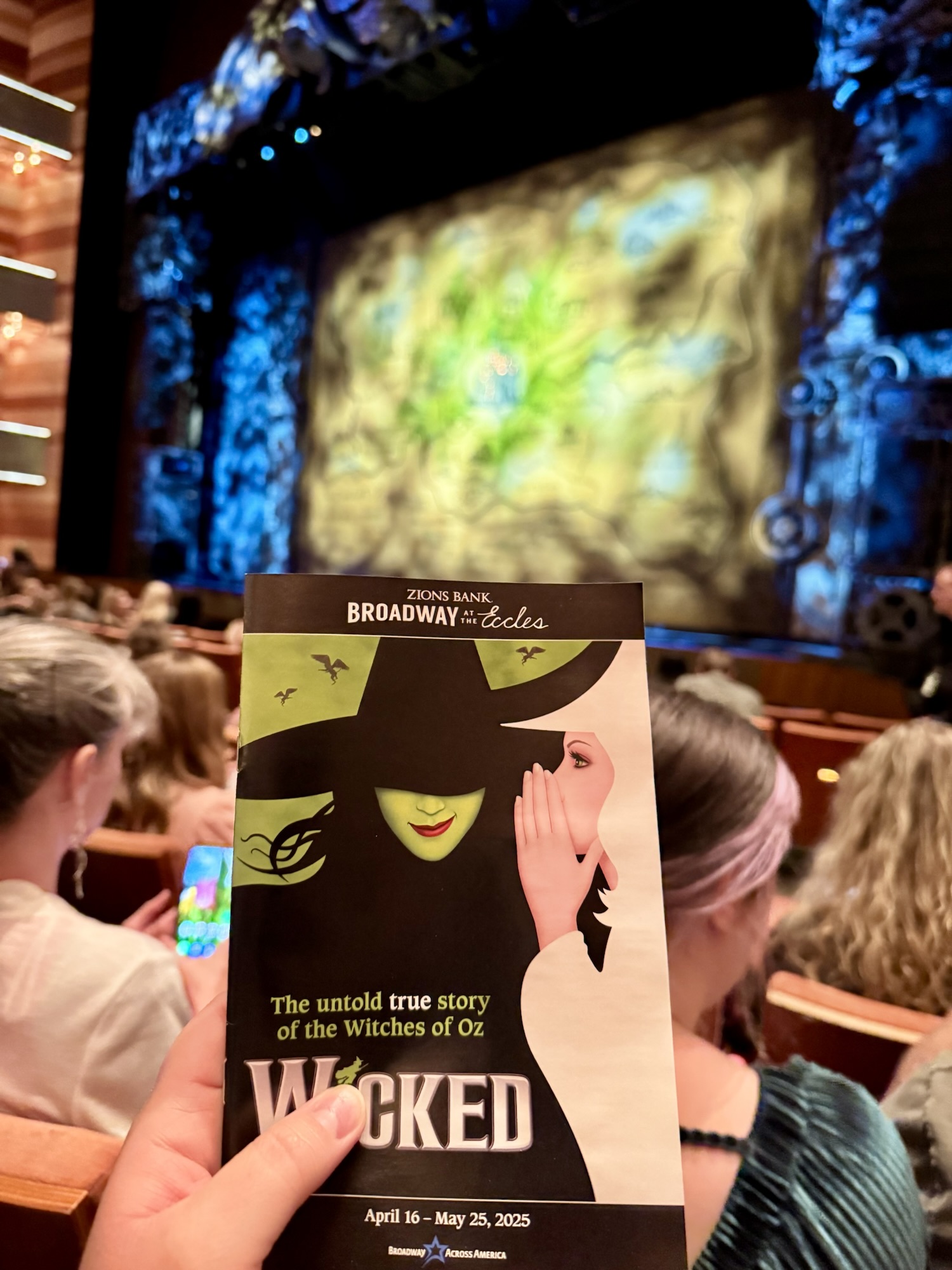

My wife and I celebrated our anniversary by attending a traveling Broadway production of Wicked at the Eccles Theater in Salt Lake City. Joined by a friend, we immersed ourselves in the vibrant world of Oz, and I was captivated. I’d seen the film “Wicked: Part One” in theaters, but it only tells half the story. I chose to wait for the full experience of the live stage production to uncover the rest, resisting the urge to spoil it online. I had my guesses—would Elphaba die? Would she and Fiyero find love? Would her friendship with Glinda endure? The answers unfolded in ways that stirred my heart, and I felt a profound kinship with Elphaba Thropp and even the flawed Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

A well-told story connects you to its characters, and Wicked does this masterfully. Elphaba, with her green skin and fierce spirit, is an outsider from the start, judged and rejected for being different. Her journey to do good, despite her mistakes and the world’s cruelty, resonated deeply with me. I’ve felt that sting of rejection, the weight of being defined by my past. Like Elphaba, I’ve made mistakes—trusted the wrong people, acted impulsively, pushed others away. Her grief over losing her sister, Nessarose, and her desperate need to hold onto her sister’s shoes as a keepsake hit close to home. I lost my brother to suicide, and I still keep his glasses to remember him. Those tangible connections to loved ones keep their memory alive, even as we navigate our pain.

Elphaba’s story reminded me of a powerful moment from the New Testament—the story of the woman caught in adultery (John 8:3–11, KJV). Under the Law of Moses, having sex outside of marriage was a serious violation of the law of chastity, deemed a sex offense and a capital crime punishable by death by stoning. The scribes and Pharisees brought her before Jesus, saying, “This woman was taken in adultery, in the very act” (John 8:4). If the people in the first century were using today’s terms, they might label her a sex offender, dehumanizing and treating her with the harshest judgement. Yet, the man involved was conspicuously absent, exposing their hypocrisy. They used her to trap Jesus, caring little for her humanity. Jesus responded with wisdom and grace: “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her” (John 8:7, KJV). One by one, the accusers left, “being convicted by their own conscience” (John 8:9, KJV). Jesus didn’t condemn her but offered compassion, saying, “Neither do I condemn thee: go, and sin no more” (John 8:11, KJV). Like Elphaba, this woman was judged harshly, yet grace gave her a path forward.

I also found myself connecting with the Wizard, a man whose terrible choices stemmed from insecurity and a desire to be loved. His self-hatred and shame mirror struggles I’ve faced. Letting go of my own shame has been a journey, one that’s taught me to extend compassion to others. Yet, I’ve seen how people respond to my past—an open window to their hearts. Some embrace me with kindness that brings tears to my eyes, treating me like a brother or friend. Others turn away, gossip, or cross the street to avoid me. It’s painful, but it reveals their spiritual state more than mine. I choose not to judge them, just as I hope not to be judged.

Wicked passes the Bechdel Test—a measure of whether two named female characters discuss something other than a man—highlighting the depth of Elphaba and Glinda’s friendship. Their bond, tested by trials but enduring, shows the power of loyalty and acceptance. It’s a reminder that stories centered on women’s relationships are rare and precious, reflecting a shift toward better representation in media.

What if Oz had embraced Elphaba from the start? How much more good could she have done if she hadn’t been pushed to the margins? Her story challenges us to look at those we judge—those we label as “wicked” based on appearances, past mistakes, or differences. Imagine the good we could unlock by offering compassion instead of stones. I think of Jesus’ teachings, like the parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37), where an outsider showed mercy when others passed by. Or the woman at the well (John 4:7–26), another outcast who Jesus met with dignity, not judgment.

The second half of Wicked surprised me in the best ways. I won’t spoil the fates of the Scarecrow, Tin Man, or Cowardly Lion, but their reveals were thrilling. I was overjoyed to see Elphaba and Fiyero find love, accepting each other despite their flaws. Glinda and Elphaba’s friendship, though strained, held strong—a testament to the power of connection over division.

As I left the Eccles Theater, I carried a renewed resolve: to be less judgmental, more compassionate, and to see people for who they are, not who they were. Elphaba’s defiance and the Wizard’s redemption remind us that we all have the capacity to change, to grow, and to do good. Let’s embrace those who are different, lift up those who’ve fallen, and offer grace to those who need it most. As Elphaba and Glinda sing in “For Good,” “Because I knew you, I have been changed for good.” Let’s change the world for good, too, one act of compassion at a time. For any ideas to make this happen, please comment below!

Photos by Jared Harding Wilson. All rights reserved.

Discover more from Hike Stars On Earth

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.